I find it more difficult to write this blog all the time. It seems the more I try to learn about complex issues, the more I recognize that I can’t say anything that hasn’t already been said with more eloquence, expertise, and meaning than I can offer. However, there are two reasons why I feel the need to add my thoughts on this and other important topics. First, as I have mentioned before, writing to a public audience, no matter how small, forces me to refine and clarify my own thoughts and forces me to challenge my own ideas. Second, I still maintain a glimmer of hope that what I write might help inform or shape someone’s opinion. Though I often see great insights on either side of a debate, I less often see commentary that helps both sides find common ground, understand each other’s perspective, or even recognize that there aren’t always two competing sides and hope that I can offer some of that perspective. With that goal in mind, I’d like to share my opinion on Colin Kaepernick’s decision to kneel during the national anthem and the Black Lives Matter movement in general. I have two general arguments I’d like to make. First, police shootings are just one symptom of the larger racial injustices that continue to exist in this country and we need to do more to recognize and alleviate these problems. Second, supporting this effort is not, or at least shouldn’t be and usually is not, anti-police or disrespectful of our military.

Let me start by offering my support of police officers and those in the difficult position of risking their lives and makings decisions about lethal force in an effort to promote peace and safety. I hope you take my profound respect for veterans as a given (my choice to serve in the military is largely influenced by the quality of people in the past and present who have made the same decision and my hope to live up to their example). I also want to emphasize that my personal opinions are not meant to represent the broader military or anyone other than myself. I hope my experience can offer some insight, though I will be the first to acknowledge that it is truly limited. While my military career has at times put me in places of increased risk to my personal safety, I have never been in a situation where I felt my life was in imminent danger, and believe we need to be very careful when judging the actions of those whose professional duty puts them in that position. As I will discuss further, I, like most other people who are sympathetic to the BLM movement or conscious of racial injustice, have no tolerance or approval for violence or anger directed at law enforcement officers, nor do I support or condone in any way violence in any form as a tactic of protest.

As I watch are re-watch the video of Terence Crutcher’s death, and consider the known and unknown details of other stories where lives were lost in encounters with police, I have several reactions. First, I believe that nearly all of our country’s police officers, including most involved in these situations, are good people trying to do the right thing, while recognizing that there are some cases of overt racism, abuses of power, or criminal negligence. Second, I recognize that there are too many cases when lethal force was inappropriately used and people were killed who did not need to die, and these cases appear to disproportionately affect black men and women. Few, if any, of these cases are as cut-and-dry as either side would portray, but many share the trend of an officer, in a time of extreme stress and perceived or actual personal danger, mistakenly overestimating the threat of an individual. I am not discounting the fact that individuals in some of the cases could have made choices to reduce the likelihood of violence, but it seems apparent that in too many cases people were killed when their actions did not at all warrant lethal force. No good officer wants to use lethal force when it is unnecessary, and whether your overriding concern is for Blue or Black lives (this is not mutually exclusive) we should all want to be a part of eliminating these tragic situations. As the general public, we have the responsibility to ensure that those entrusted with the right to use lethal force have the tools and training to do so appropriately. To meet that responsibility, we must ask two very important questions about these situations: 1) was race a factor? and 2) how can similar outcomes be avoided?

When we try to decide if race was a factor, we must acknowledge that we cannot know the answer in most individual situations. The person who pulls the trigger is affected by hundreds of subconscious cues that even they are unaware of, and we can never know nor should we try to judge their thoughts. We can, however, look at overall data to determine if unnecessary force is used more commonly against black individuals. These data provides evidence that race is indeed a factor, though the issue is of course complex. First, we don’t have good, comprehensive, and timely data, and even if we did it’s hard to determine the role of race. Several trends, however, are clear in the data we do have. First, police use lethal force in our country at a far, far greater rate than any other developed country. The police killed almost 1,000 people in the United States in 2015, and about 10% of them were unarmed. While I personally believe that in most cases police were making the best decision possible according to their training and the situation, we have to ask ourselves if the nature of policing across our country could be changed to reduce violence and killings in general. In the years following 9/11, there are more unarmed people killed by police every year in the US than those killed by terrorists, so I don’t think it’s unfair to make police violence a priority. Second, lethal force is directed at African Americans (and particularly black males) at a greater rate than other groups, even though most people killed by police are white (African Americans make up 24% of those killed by police and only 13% of the total population). Lastly, police have more encounters with African Americans than other groups, and thus it is difficult to empirically determine if police officers are systematically biased or whether the increased violence against African Americans is just the result of more police interaction.

The BLM movement has focused a lot of attention on police violence, but this is just a symptom of the much greater issues of equal opportunity and racial justice that I want to discuss first. Police violence is one of many areas where social outcomes are affected by race. African-Americans have a lower probability of “success” in the US than other groups by many measures (see here or here for discussions on wealth, income and education, or here for incarceration). The point of these data is not to support the inaccurate stereotype of the Black community as poor and crime-ridden, to ignore the vast majority of African-Americans who are successful in multiple ways, nor to ignore the difficulties many disadvantaged white individuals face, but simply to highlight the reality that African-Americans have a systematically lower probability of good outcomes in our country. This is a fact that I believe can only be explained by the continuing existence of racism – in various forms – in our country, and I would like to walk you through a basic exercise in social science to make that argument. First, we have to ignore individual cases and look at overall distributions. Those trying to downplay to role of racism often correctly point out the many individuals who are both black and successful or white and unsuccessful, but such arguments ignore the empirical reality that race is systematically related to outcomes in the overall population. Race does matter, that is not an opinion or even an argument, but an empirical observation. This is why colorblindness is a prevalent form of racism, one that I have been very guilty of in my life. This is also why acknowledging the existence of white privilege is important, but is not meant to blame any individual for being white or for the challenges facing people of color, nor to imply that white people don’t face challenges, it simply acknowledges that there is an advantage to being white in this country that may not completely determine success, but systematically influences outcomes by removing obstacles that are commonly faced by people of color.

Once we acknowledge this reality, we have to explain it if we want to resolve it. If you believe, and I hope you do, that people are equally capable of and interested in success under the same conditions regardless of race, it seems obvious that African-Americans, as a group, must not be facing the same conditions as everyone else in this country. The rejection of this premise is the essence of what I would call old-fashioned racism, the idea that being black makes someone less capable of or interested in some kind of success (old-fashioned not because it no longer exists, but because we’d like to think it is only historic). Some might say they reject this form of racism and argue that choice, rather that external conditions, lead to the disparity (i.e. people could get an education, a good job, avoid crime, leave struggling neighborhoods, etc., but choose not to), but that seems dangerously similar when you think in terms of distributions rather than individuals. Yes, any individual might be able to make such choices and we should encourage people to do so, but how can we believe that a racial group systematically makes ‘worse’ choices without acknowledging external conditions or relying on old-fashioned racism? If we choose to reject this form of racism, uncomfortable logic forces us to acknowledge either 1) African-Americans make similar choices but are actively discriminated against or 2) being black is associated with several other structural factors that change decision-making incentives and cause poorer outcomes, or 3) some combination of both.

Explanation #1 is what I will call active racism or discrimination. We can argue about the extent of active racism, but might agree that there is less than there used to be, but it is by no means eradicated. If active racism is causing poorer incomes, more incarceration, or more police shootings, I hope you believe we need to do something about it. However, even if it’s not, or even if active racism is only a minor or fringe problem, we still have to deal with explanation #2, which I will call structural racism. By this I mean the racial advantages and disadvantages that are not the result of active discrimination, but rather the historic and cumulative effects of social, economic, and political systems that produced and reinforced racial disparities in power and opportunity. This structural racism is still a major issue for several reasons. One is implicit bias, the subconscious value we place on race without even knowing it. The human brain is amazing, but full of biases and blind spots. It sees patterns and infers information from limited data, making us think we know all kinds of things that we don’t actually know or are just wrong. This allows us to make thousands of split-second and unconscious decisions that are generally helpful, but sometimes incredibly wrong. (Check out Thinking Fast and Slow, Blink, or Being Wrong for great reading in this area.) Since our society is still so segregated, many white people don’t have daily positive interactions with people of color for much of their life. Instead, they are bombarded with negative stereotypes from hundreds of years of racist ideas that are reinforced by media, entertainment, and other sources. The national heroes and role models presented in literature, education, and history are overwhelmingly white, another reason most Americans have few positive associations with people of color in any form. In the absence of positive experiences and education, we begin to associate black skin and faces with negative thoughts like fear, risk, danger, crime, or poverty – and this unconscious perception is amplified by empirical observations that are the result of structural racism. If you find that hard to believe, please take an implicit bias test or look at results from such tests – implicit bias is very pervasive. If you think these biases don’t matter, look at this study that shows that otherwise identical resumes were 50% more likely to get a callback from real companies for an interview for real job postings if they had typically white rather than commonly black names. As personal, albeit anecdotal, evidence, I can attest to the reactions of fear or avoidance my daughter gets every time she walks into a new classroom. This isn’t because 5-year old children are active racists, but because my daughter is often the first black person they’ve ever interacted with in our segregated world and it takes time and effort to overcome the implicit biases we all soak in. The tragic death of Trayvon Martin makes it clear that such bias is a danger to people of color, a danger that I and other parents of brown children take very seriously. White privilege in our racially-mixed family means that some of my children will get to wear hoodies without considering if it will make them targets for overzealous neighborhood watchers. It also means I will have to teach my other children that while I am willing, obligated, and proud to fight to protect the Constitution and have great respect for others who made a greater sacrifice, they need to swallow their pride, ignore their justified indignation, and keep their mouth shut if their fourth amendment rights are violated by stop-and-frisk policing that targets them for looking suspiciously black. This is also why labels like All or Blue Lives Matter, while of course true on their face, can be very frustrating even to someone like me who is extremely supportive of law enforcement, because they are often used to purposefully obscure the continuing role or racism, blame those who peacefully call for racial equity for violent tactics they don’t support, or simply ignore the root causes of racial tension and injustice. Overcoming this structural racism is why I, and many others, believe it is important to recognize the role of race and intentionally celebrate the achievements of people of color, because it makes a difference when my daughter sees a woman win a gold medal and can say, “she’s like me, she is brown and her hair grows up instead of down,” and because I didn’t even begin to understand the biases I had and the injustices I ignored until it started hitting closer to home. When our collective brains begin to unconsciously associate being black with national heroes, Olympic champions, and professional success instead of crime, poverty, fear, and risk we will finally chip away at structural racism – but Black Lives won’t fully matter like they should until then.

Beyond implicit bias, structural racism also affects incentives and opportunities. African-Americans are more likely to be born in communities with poor services and underfunded schools and into families who are still suffering the generational consequences of systematic racial oppression. I personally believe that anyone in our country can be successful with hard work and good choices, but I have to wonder if I would have had such faith if my skin were a different color. If my parents had been born black in pre-Civil Rights America (because that’s when they were born – let’s not forget how recently Jim Crow ruled), would they have instilled in me those values and would I be passing them on to my children? Would they have taught me to unquestionably respect authority, or might I have been more likely to respond with fear, anger, or indignation to the symbols of my family’s historic oppression (police)? Would I have had teachers, coaches, Boy Scout leaders, and dozens of other people continually telling me what I could achieve, or might I have been a little more likely to come to the conclusion that skin color was more important than personal choice in determining the future? Would I have been quicker to turn to crime instead of education and employment when I noticed the empirical truth that even having a commonly black name makes it harder to get a decent job? I want to convince every person in this country that they can be successful with hard work and good choices regardless of their race, but more important than convincing people it’s true is making sure it’s actually true.

Now back to police violence. Even if the violence toward people of color is a result of increased encounters with police and has nothing to do with active racism, the problem still has roots in structural racism and needs to be addressed. In each of these police shootings, we can probably all agree that both the officer and the victim were under extreme stress. They both were making decisions not based solely on thorough analysis and rational thought, but on their instantaneous perception of their situation, falling back on years of personal experience, instinct, and hopefully extensive training in the case of the police officer. I have had to employ lethal force in my career, and believe most people with similar experiences wish we could have frozen time and carefully considered all the information we did and didn’t have to make sure we made the right choice, but instead were forced to make a split second decision when our own judgement was affected by extreme stress. I can only imagine how such feelings are amplified when you believe your life is in imminent danger, something most of us have never experienced and thus we should be very wary of our own arm-chair, retrospective judgements of someone else’s actions. Thus, I think arguments about whether the officer should have noticed a specific detail (it wasn’t a real gun, he was scared not angry, the window was closed, etc.) are a little ridiculous, and claims of individual racism are generally unhelpful. The officer clearly felt their life was in danger and they needed to kill someone, and hindsight ultimately showed that they made an incorrect assessment. While we need to prosecute and eradicate criminal negligence and abuse, we shouldn’t vilify officers who made the best judgement call they could in a horrible situation. Instead, we need to understand why the incorrect judgement happened and try to prevent it in the future through education and training.

First, we need to understand that structural racism leads to different reactions to police. If I encounter the police, I unquestionably believe that exact cooperation will always lead to a just and appropriate response from them (something I teach my black and mixed children, unfortunately as much out of fear for their safety as a matter of trust). However, it’s clear that such a belief was unfounded for African-Americans in our recent history, and some believe it is still not accurate. When exactly was the day that we could trust all police to judge people fairly, independent of their skin color? Was it in 1968, the day President Obama was elected, or is it possible that, at least in some parts of our country, it still hasn’t arrived? While I firmly believe we must teach everyone to respect police officers – preferably out of principle, but at least out of self-interest – we must also ensure that our police are rightfully earning that respect and be understanding when people are slow to regain trust after generations of oppression. Maybe an unarmed black man behaves erratically in front of police not because he’s a “bad dude,” but because his life experiences have taught him to trust fear over fairness.

Now we turn to the police officer’s perspective. Police are regularly encountering situations where they have no information about a person other than the color of their skin and then are forced to make an assessment about the risk that person poses. As Trevor Noah does a good job of saying with only a little satire and bias, when most police officers’ encounters with black people involve crime, why wouldn’t they develop inaccurate biases and be a little more likely to assume someone black is dangerous? Even in the absence of any active racism, darker skin will be implicitly associated with higher risk in our country because of the legacy of structural racism, which has a role in both this implicit bias and the fact that African-Americans have more negative encounters with police because of different opportunities and incentives. We can expect good police officers to systematically make more inaccurate judgements when race is a factor unless we put a lot of work into overcoming the automatic biases that we can’t control. No individual is at fault for the unconscious biases they possess, but we have to work to acknowledge and deal with them. We also have to make a huge effort to change the structural conditions that affect opportunities, since our government set in motion those conditions.

The argument I am trying to make is that even if active or conscious racism isn’t a factor in these shootings, and even though I wholeheartedly support the police and sympathize with the difficult situations they face, I still believe that being brown or black in this country is inherently more dangerous and difficult than being white, and that means we are not living up to our constitutional values of equal justice and opportunity. I do not expect others to agree with this conclusion. You might believe that there is no racial injustice or that highlighting the role of race furthers racial divisions. I understand that some people feel supporting BLM incites violence against police and makes their job more dangerous. I cannot deny this is a possibility and, like everyone else, am extremely saddened by the killing of police officers in Dallas. I also believe, though, that the bigger danger is associating this individual’s violence with the broader, peaceful BLM protests, or ignoring racial tensions altogether. If we try to claim that race doesn’t matter in the face of the empirical reality that it does, racial tensions and divisions will only increase and intensify. If we ignore the proposed solutions or try to silence legitimate concerns and peaceful protests, we will not only continue in a world where opportunities are influenced by skin color, but we will invite more radical responses from those who refuse to live under such conditions. Police officers, like those in the military, knowingly choose to accept risks in order to protect public values, and we can’t allow the fear of radical violence to silence a peaceful discussion about those values. We must marginalize the violence by listening to those who carefully choose to express their concern with racial injustice without attacking the police. I believe this is what most of the BLM movement is doing, though there will always be individual actors who choose violence instead of peaceful protest – we cannot lump those groups together even if it seems they have a common cause.

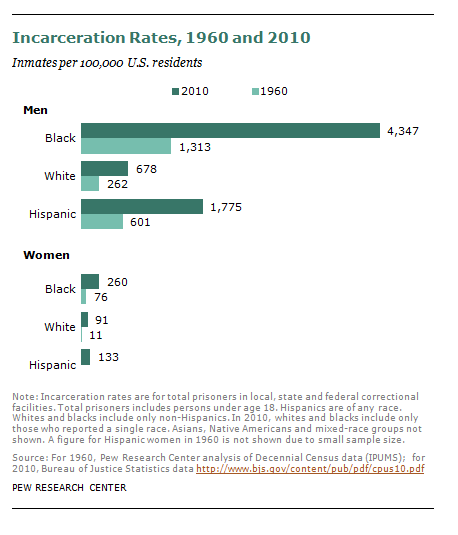

That is why I have respect for (though maybe not total agreement with) the many people who are following Colin Kaepernick’s lead in kneeling for the national anthem. I do not know their character or motives, but believe this protest is not about disrespecting the values of our nation or the people who fought for them, but rather bringing attention to the fact that we are not living up to those values. As a military member, I of course support and defend the Constitutional right to make such protests. In addition, I personally believe that one can honor the sacrifices of those who have fought for our nation while simultaneously recognizing that we have not yet fully achieved the things for which they fought. The protest could easily be seen as a form of respect, believing that our flag symbolizes something important, that we honor those who have sacrificed for it, but that we are not currently doing our part to live up to their sacrifice. I understand that many people feel a protest or statement could be made without an act that is perceived by so many as disrespectful to veterans. In fact, I personally agree, though I recognize that the protest is more effective precisely because some take it as offensive. It captures the attention of those who treasure the symbolic meaning of our flag, and forces us to have a discussion we might not have if a less controversial method was chosen. Regardless of our opinion, however, I would hope that rather than attack those who are trying to make such arguments, we would instead discuss meaningful alternatives for healing the racial tensions, segregation, and disparate social outcomes that undeniably exist in our country. I don’t think we can just ignore race and hope things get better. These charts, along with the one below, show that many meaningful racial disparities have not improved since the time when segregation was still legal. Police shootings are one symptom of this deeper problem, and are just the catalyst for people to once again say that we’ve waited long enough for true racial equity.

So what is the solution? How do we prevent this from happening again, and again? Campaign Zero, in my opinion, has some of the most reasonable solutions for addressing police violence. I do not agree with all their suggestions, but also don’t believe any of them are anti-police. Some focus on reducing negative encounters by changing the way we police (ending for-profit and broken window policing), some focus on reducing the absolute level of violence (changing the standards for use of force, providing non-lethal alternatives), and some focus on accountability and training (oversight/body cameras). At a minimum, I think it is in the interest of police and the public to make some of these recommendations into national standards and increase the amount of data we collect and training we provide to address the issue. These are the kind of common-sense solutions that should be discussed and debated, but cannot be ignored – they are important measures that would improve the situation. None of these, however, addresses the true root causes of structural racism which will require long-term investment. The Movement for Black Lives has a policy platform that addresses structural racism more comprehensively. Many people, including myself, would probably see some of the recommendations as radical, but we must recognize what the legacy of racism has taken away from African-Americans and how much is required to restore true equity. Unlike the M4BL agenda, I don’t think these efforts should be racially targeted at the individual level, but I do believe we need significant public investment in areas where racial divisions are apparent and have lasting consequences. The two area that I think are critically and urgently important are education and criminal justice. We need to make sure that children are getting the same quality public education regardless of their race, which in our country means regardless of zip code. I am not an education expert and won’t propose details, but in general believe that more centralized and equalized funding (emphasis on more and equal) without centralized control is probably the right direction. Education is mostly locally funded in our country which has many great benefits but also perpetuates cycles of unequal opportunity. People with resources move to places with good schools and the schools get better, while people with fewer resources stay in places where it is increasingly difficult to improve education. This creates strong incentives for geographic stratification and segregation, especially when the initial conditions of segregation were set by actively racist government policy. How to change this is beyond my expertise, but regardless of the details we have to invest more in education in the parts of our country where opportunities are most limited.

The racial disparity in incarceration in our country (as well as the total incarceration rate) is absurd as the chart below shows. I have no expertise in this area either, but after spending some volunteer time in prisons I have come away with one major observation – just about everything about being in a “correctional” facility makes people more likely to commit crime in the future. Our solution to crime in this country seems to be to ignore all root causes, then throw as many people as possible in prisons that make them more likely to commit more crime. Even if we completely ignore any moral considerations, this is wildly inefficient from a public policy standpoint and every other country in the world has lower incarceration rates without more crime (we now have more people in prison in this country than Stalin’s Gulag). We have to rethink how we deal with crime, address root causes rather than throw more people in prison for longer (mental health care, drug addiction services, etc.), and make prisons a place that reduce the likelihood of criminal behavior (e.g. prison means education, training, and work experience, not dehumanizing). This won’t happen just by ending private prisons, but will require a major investment and change of attitude that will pay future dividends for our society and reduce the cycles that perpetuate racial divisions.

So I believe that #BlackLivesMatter while supporting our police. I have a profound gratitude for people who sacrificed to make this a country of incredible opportunity, while also respecting those who won’t stand for the flag when they believe those opportunities are influenced by race. I don’t think it’s useful to discuss how individual racism may or may not have been a factor in police shootings, nor is it helpful to turn our anger towards either the police officers making difficult decisions or the protesters demanding accountability. I do believe it is imperative to focus on the root causes of racial divisions in our society and invest in areas that will erode the persistent effects of structural racism. I will teach my black, brown, and white children that they must trust and respect law enforcement, while recognizing that they may be treated differently, even by good officers, because of the color of their skin. I will raise my voice to remedy that injustice while condemning any violence in supposed support of that cause. I will teach all my children, and anyone else who will listen, that they can achieve happiness and success as they define it through hard work and good choices, knowing that some of them may face more obstacles and have to work harder than others because of their race. I will celebrate heroes who overcome similar obstacles, honor those who fought for important values even when they were not yet fully attained, and recognize how my own race may have effected success in my life while trying to raise awareness and find solutions to the continuing effects of structural racism in hopes that one day race will not be a factor in social outcomes.

Also published on Medium.