After a long hiatus, I am attempting to restart this blog. I took a break in the hopes of working on a book, but then I started a Ph.D. program, went from three children to five, and started a non-profit, so the ‘write a book in my free time’ plan went down the drain. I am going to start sharing some opinions related to the current election, but do so very hesitantly for several reasons. The first is that if my doctoral studies have taught me anything, it’s that I don’t know anything (though I am increasingly suspicious that no one else does either). I hesitate to share my own ignorance and reserve the right to update my opinions with new information, but also know that writing, sharing, and receiving feedback on my ideas is the only way to overcome that ignorance. I also hesitate because this election, like others but possibly to a greater extent, is divisive and charged with emotion, and I am by no means impartial on the subject. I hope that I can share my convictions with respect and civility and provide an opportunity to further an important discussion within those bounds.

With that introduction, I will jump right into my topic: the possibility of a major third party. With so many people unhappy with either of the major party nominees, it seems like a reasonable time to consider the prospects of a successful third party. I think a major competitor to the Republican and Democratic parties is extremely unlikely, but I’ll at least offer my opinion for what might make one more likely or successful. I will leave the discussion of Trump vs. Clinton for another day, though I plan to share my extremely strong convictions on that topic once I feel I can do so in a way that is respectful and informed (spoiler: I’m not a fan of Donald Trump and will vote for Hillary without a doubt if it is her vs. him). For now, let me take as my starting point the fact that many people are unimpressed by the current candidates, frustrated with the options created by our current dominant parties, and hoping for something better. In this post, I’ll build an academic and theoretical foundation that will inform my next post which will propose my hope for a third party, the one I’d vote for if it emerged. If you’d like to skip the academic paragraphs and jump to where I tell you how the world could be better, click here.

First, another more specific disclaimer on my own ignorance is necessary. I now have a Master’s degree in political science and will soon have a Ph.D. (hopefully), but my focus is on comparative and African politics – I have not taken a single class in American politics or political theory, nor do I have any real experience in these areas, so I don’t want you to confuse me with someone who knows what they are talking about. I am no more than an amateur or hobbyist in these areas – so please take my opinion as such.

With that in mind, let me share a little about the function that a political party should serve. In a perfect world (at least my perfect world), where most citizens were actively politically engaged, people would have a very diverse set of opinions, policy preferences, and priorities on several issues, informed by a diverse set of factors. Since many of these preferences would conflict, it would of course be impossible for any party to make everyone happy. Political parties would emerge with platforms of preferences that they felt represented a large group. Each citizen would examine the several platforms, and choose the one which most closely matched her preferences, knowing that some would align better than others, though none might align perfectly, and the result would be a competition among parties to aggregate diverse interests in the most efficient way possible. In reality though, we don’t live in a perfect world where everyone is engaged, comes up with their own independent preferences, and then aligns themselves with the party that represents those preferences. Because of other priorities we often just don’t have the time, energy, ability, or inclination to independently research every issue – so we look for shortcuts like ideology or principle, or even who our family or friends vote for. For example, I might find that, in general, I tend to support smaller government or broader social services, or tend to listen to and respect people with that opinion. I might be more socially conservative or liberal, more hawkish or dovish. Some people might join one party or the other because they really care about one issue like the environment or abortion more than anything else, but most people pick a side based on where they find themselves on a continuum of ideology, sometimes, if not often, based more on superficial feelings of political identity than on an independent examination of the issues. This is most often represented in the standard left-right continuum of politics. So we busy people just decide that we are on the left or right and pick the party on that side. This is not necessarily bad (though you can read about my personal concerns here), it is actually usually efficient and fancy analysis like game theory will tell you this can and often does lead to the best possible outcome. But sometimes it doesn’t – sometimes it leads to Trump (which I will call a suboptimal outcome, though I welcome conflicting opinions). So why doesn’t some reasonable person or party come along and put themselves right in the middle of this left-right business and stop all the fighting? To answer that, we need some political science knowledge.

Social science in general is very messy, and it’s tough to come up with any solid conclusions because the world is full of seven billion variables (people) and nothing ever happens twice, but there are a few “laws” of political science that are pretty reliable. One of these is called Duverger’s Law, which basically tells us that in a country like America where you have a majoritarian rather than proportional representation system you are likely to only get two viable parties. The reason is simple. In a proportional representation system a party can get 30% of the vote in a given district and get 30% of the representation so people will vote for it even if it can’t get a majority. Thus, people will align themselves with a party that closely represents their personal preferences even if they are in the minority. In America, however, 49% of the vote in a given district gets you exactly nothing if the other party has 51%. Thus, no one has an incentive to vote for a party unless they have a chance of getting the majority of the vote. If my preferred party is only attractive to 35% of the people, it does me no good to support it. In the long run all minority parties have an incentive to build coalitions and compete for 51% of the vote, leading to broad majority parties that don’t closely match a lot of peoples’ preferences. But why can’t a party just form right in the middle and force a split of the extreme right and left? The figure below illustrates why this doesn’t happen.

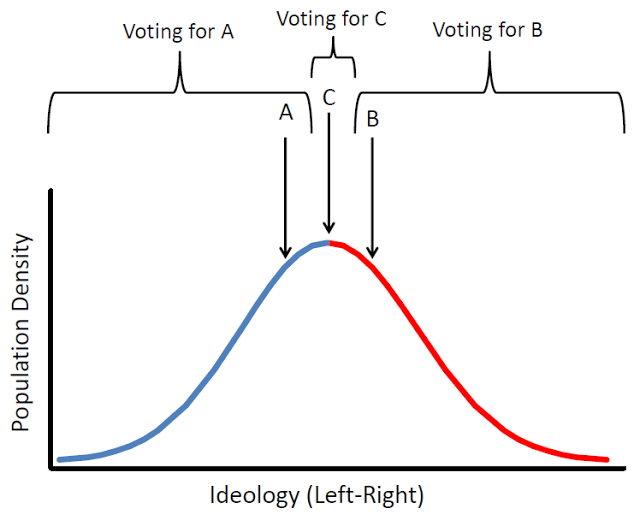

The curve represents public ideology, some on the extreme right and left with most in the middle. One party choses point A, left of center, as their platform and one chooses point B, right of center. Reasonable party C comes along and goes for the middle. Now everybody votes for the party closest to their own personal ideology. A and B get everyone on the extremes plus half the distance to the middle, while C only gets half the distance to each other party. As long as A and B aren’t crazy far apart, C never has a chance. But, you might think, A and B are crazy far apart in our country and C should have a chance. There are two rebuttals to that. One: the Republicans and Democrats, despite all their fighting, aren’t actually that far apart, and they creep towards the middle as the general election comes closer. Two: if the American population is polarized (think of a bimodal or two humped rather than normal curve), then the parties can be far apart and C still has no chance since there are more people at the extremes than the center. Although as of 2008 there are more Independents than Republicans or Democrats in this country, ideological polarization has been steadily growing, meaning that people don’t like the parties but are still strongly on the right or left ideologically. For these reasons, the two main parties have an incentive to find a place far enough to the right or left to distinguish themselves, but close enough to the center that a centrist party has no chance and anyone to the extreme left or right will just vote for the dominant party even though they don’t like it because minority parties have no chance. If a minority party forms at either extreme (e.g. the Tea Party), there will be extreme pressure for A or B to align with it, otherwise they will split the vote and both lose to the other major party.

So, even if my preferences align with a minority party, in the end minority parties and their supporters will ultimately align with the broader coalitions of the Republican or Democratic parties. The best a centrist party could hope to do is never win but force the other parties to come closer to the center. This law is not exactly as reliable as gravity or supply and demand, but almost; so complaining about it will do you about as much good as complaining about the salaries of professional athletes. The most realistic way to change the fact that the current Republican and Democratic parties dominate is to completely change the American democratic system to proportional representation (like much of continental Europe). I’m not opposed to that, but everyone else might be and it’s probably just not going to happen.

So how do we change things, given that many people don’t like the current outcome and a centrist party is unlikely? I think one possibility is to realign the broad coalitions, and this has in fact happened several times throughout American history. The trick is to realize that there isn’t just a one dimensional continuum of right and left, there are actually multiple dimensions. For example, I might be economically to the right (I like small government), but socially to the left (I support same-sex marriage). I could be to the left on most issues, but very supportive of free trade (the Clintons), or right on some issues, but hate free trade (Trump). Some issues might not even be dichotomous. When it comes to defense, one could make a continuum between hawkish and dovish, or you could choose between isolationist, internationalist, and interventionist, or give up on conventional labels and just call yourself a pragmatist. The current parties are actually coalitions of smaller groups from across these dimensions, creating an artificial one-dimensional divide across multiple issues. A new party, then, could try to build a new coalition from different places on different or multiple dimensions instead of picking a spot on the existing left-right continuum. They could do this by trying to redefine the important dimension, by trying to appeal to multiple dimensions, or some combination of both.

I believe the Libertarian movement has had some (albeit modest) success among minority parties because they try to exploit this idea of challenging the existing Left-Right divide. Libertarians, in the words of candidate Gary Johnson are, “broadly speaking, fiscally conservative and socially liberal,” in that they want government influence out of all aspects of individual life as much as possible. Many support free markets (like mainstream Republicans) and are more likely to oppose government regulation on social issues such as immigration or abortion (like mainstream Democrats). They essentially try to redefine the current divide between the major parties by highlighting divides across two dimensions – social and economic. This might attract people from both parties, but has not done so in mass yet. While in some ways the Libertarian party simply creates a different one-dimensional divide, it also uses that change in focus to redefine the debate in other issues that don’t fit neatly on that dimension, such as national defense. They can thus capture a base of people that really believe in limited government while also trying to appeal to a group that doesn’t care about that distinction but likes the policy platforms they formulate about how to deal with international terrorism or other issues. This seems to me to be the most likely strategy for the emergence of an alternative party: focus on a particular ideological divide to create an identity, and then develop policies on other issues that appeal to broader groups across existing divides. An unlikely, though theoretically possible, prospect is that a party or multiple parties with this strategy could cash in on the mass discontent with the current coalitions, gathering support until they reach a tipping point where people believe they could challenge the major parties. This will only happen though, if the American public responds to this new alignment. So, if we truly want an alternative to the two dominant parties, we must refuse to accept the current ideological divide. We must be dissatisfied not just with the current parties, but with the current Left-Right divide. That’s why I cringe every time I hear someone say something to the effect of, “we need a truly conservative or truly liberal party/candidate,” or when I see the data that we as Americans don’t like the parties but are still ideologically polarized, still firmly on the Left or Right, just angry that the parties aren’t in the same place as us. What we really need is to refuse to be one-dimensional, to refuse not just the parties or their candidates, but the concept that one particular idea, ideology, or assumption (like smaller government or less corporate power) can help us solve all the complex issues of government.

That’s long enough for this post, but in the next I will build on this theoretical foundation and take on the role as advocate for my preferred new party, proposing the policy platform, underlying ideology, and practical road map for the kind of party I would like to see rise in prominence in American politics. I will build on reflections from the ongoing election and the theoretical base in this post to try, like Steve Jobs, to sell you something you didn’t know you wanted.

The road well traveled isn’t always the smoothest one.

– – – pretty astute, huh?

Ombtc

Interesting reading

Anyway you can set up an RSS feed? That is my preferred way of reading blogs, and would love to keep following yours. Thanks!

The RSS feed has always been active, but I’ve also added the RSS button on the sidebar. Please let me know if you have any trouble subscribing.

As you mentioned in your post, proportional representation systems tend to result in multi-party government. Accordingly, I think the U.S. should adopt such as system.

So do I, but I think it’d be pretty tough to get enough support for that.